Film Review: Embrace of the Serpent (2015) by Ciro Guerra

July 2021

Text by Ignacio Hitters

“Knowledge belongs to all. You do not understand that. You are just a white man.”

“I wasn’t meant to teach my people. I was meant to teach you.”

“The Amazon Rubber Boom” was a complex period in time. Right after the industrial revolution, the demand for pure rubber as a resource caused thousands of Europeans to travel to the Amazon forest in search of rubber trees, from which to harvest raw materials that could be traded and sold worldwide. This caused an expansion of colonialism in South America, the growth of entire cities, and the destruction of entire indigenous societies. Set around the 1900s, “Embrace of the Serpent” is a black and white movie directed by Colombian filmmaker Ciro Guerra, and could be interpreted as a tribute to all the Amazonian tribes - and the cultures they’ve created - that have been lost, not only over time, but to colonialism, slavery, and genocide.

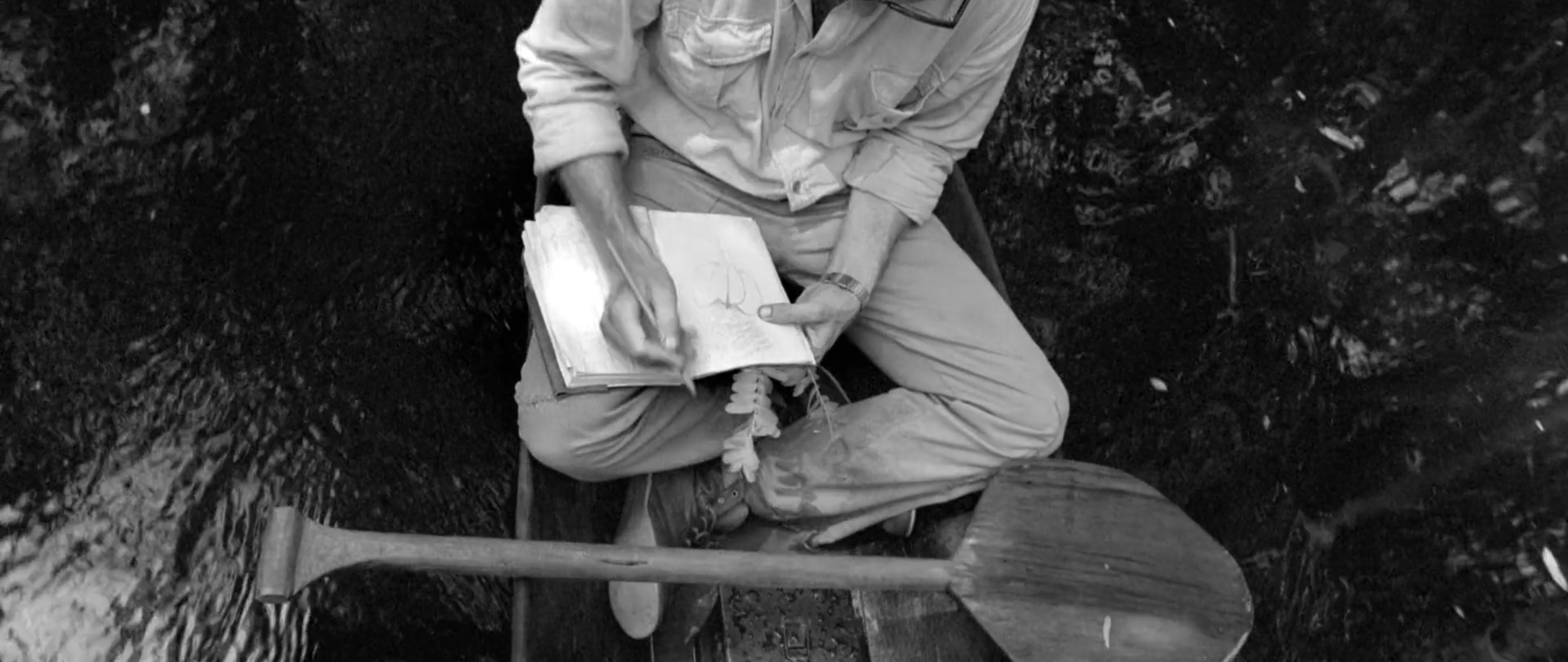

Inspired by the travel diaries of German scientists Theodor Koch-Grünberg and Richard Evans Schulte, the story follows Karamakate, an Amazonian shaman. Being the last of his kind, Karamakate lives alone in the jungle, until a visit from dying German scientist Theo disturbs his peace. With the promise of possibly finding the remnants of his tribe, Karamakate embarks on a quest through the jungle in search for “yakruna”, a sacred healing plant culturally important to his tribe, and supposedly the only thing able to save Theo. Thirty years later, Evan, an American botanist, finds Karamakate for the exact same reason - finding the sacred plant - but for a very different purpose. The two stories are intertwined between each other in a quite straightforward way, all while telling a tale of change, destruction, pain, beauty, and redemption.

On his ways through both journeys, Karamakate and company find a lot of interesting, albeit horrifying sights. Mass graves are seen between torn trees, remnants of the forced labor that came with the “rubber tapping”. Men begging to be killed for dropping a bucket of rubber, knowing that their faith against the rubber barons would include brutal torture along with death itself. A Spanish Catholic Mission led by a sadistic priest, who whips the orphaned boys for “pagan” behavior as he deems fit. This is all strongly contrasted by the absolute beauty of the jungle itself. Its dense forest, the roaring rivers that flow and the steep mountains in the distance. Beauty that is enhanced by Karamakate’s deep understanding of his surroundings, their sustainability and the respect necessary to interact with them.

One of the movie’s highest achievements is the way the cultural disconnect between the “westernized” and the indigenous is portrayed. Not only priorities differ strongly, but also simple understandings of what a concept means, or what an object is supposed to represent. On Karamakate’s side, you have a character who had to let go of everything, because the whole world he once knew was destroyed by “the white man”. On the other side, you have Theodor who, though in his own way respectful of what’s around him, and (mostly) well-intentioned during events of the film, cannot let go of his European roots, no matter how essential to his survival. The middle ground between them is the character of Manduca, a westernized local who was saved from a rubber plantation by Theodore, and at points, their voice of reason. He understands that in order to learn from such a different culture, compromises must be made, and not everyone can come out winning. Karamakate refuses to accept this, leading him through the pathway of always being an outsider, and only knowing (and slowly forgetting over time) what he’s learned so many years ago from his tribe.

Karamakate’s choices during his younger years, though always poetic, are not necessarily always the correct ones, letting go of his rationality in exchange for uncontrollable passion. However, older and wiser Karamakate learns from his past mistakes, offering an interesting contrast and what I consider to be moments of excellent character development, such as the difference between his younger-days conversations with Theo and the older ones with Evan. Younger Karamakate also contradicts himself a lot, first telling Theo that “knowledge belongs to all” when Theo refuses to leave behind his compass as a gift to a tribe, while afterwards refusing to share information on the healing plant, and burning it in a fit of rage when he realizes that people were growing it themselves, an action which was forbidden to his tribe. Even when well-intentioned, actions always have consequences, and one always has to live with the weight of them.

Instead of offering a historically accurate portrayal of the events, the film feels way more like an old fable, or a legend told by the Indigenous people themselves. Having such a perspective was a huge risk taken by Guerra that ultimately pays off. The psychedelic undertones mixed with the rawness of the jungles really makes the feel of the film be dynamic, and most importantly, very original. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a movie that legitimately tries to encapsulate the feelings of these Indigenous people without coming off as exploitative or tonedeaf. It truly feels like it was made with utmost respect for the cultures it speaks about, which is sadly a rare occurrence in cinema, especially with topics similar to this one.

It’s not surprising at all that this movie got as much critical acclaim when it was released, having been nominated to an Oscar (and being the first Colombian movie to ever have), winning the “Art Cinema Award” at Cannes and the “Alfred P. Sloan Prize” at Sundance, between multiple other accolades. However, I don’t think it’s a perfect movie. Like many other films of its kind, it’s arguably fifteen minutes too long, with some scenes feeling a bit repetitive, even if intentionally so. I also feel like at some points, a bit more of subtlety could’ve been very beneficial to the script. While the film’s topics are indeed at points served in a silver platter, writer/director Guerra still has a lot of substance to offer here. Plus, the fact that the movie is so in-your-face causes some of its impact to be enhanced and the story to be easily digestible. Even though the images look quite arthouse, drawing clear visual inspirations from legendary photographer Sebastião Salgado or filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, I assure you that this movie can be understood (and even enjoyed!) by very casual audiences as well. It’s actually nice to find a movie with such characteristics, as there’s a bit of something for everyone. Art enthusiasts, photography nerds, history nerds, cinema buffs, and people who just want to appreciate very-well-made film, don’t miss out on this one.