Valentina Lopez Aldao, Multitud en Garzón

Excerpts from an interview by Luz Hitters

May 2020

It could be argued that one of art’s main roles is to convey the current ebbs and flows of society. Specifically, a recurrent topic amongst contemporary artists is the portrayal of dystopian scenes regarding climate change.

We as a society are increasingly reminded of the consequences of the Anthropocene. In the case of art, most times this reminder is forthright, and instead the issue is tackled explicitly in an almost confrontative way. Accordingly, this pushiness restricts personal reflection, denying the beholder to recognise the human ambivalence to change and how deeply rooted the shift must be.

Valentina Lopez Aldao’s (b. 1986, Caracas) artworks stand in stark contrast as an open work; each viewer reaches her piece’s portrayal via their own critical thinking. The Uruguayan artist depicts the beach in Montevideo where she grew up, and the different characters that she sees coming and going. She makes use of several media to explore the impact of these masses and their complexity. Her exhibition Multitud en Garzón (2019), initially created for the Engelman-Ost collection, curated by Jaqueline Lacasa at Black Gallery, invites viewers to reflect on their relationship with the beach. The exhibition takes place in a small and remote town of 200 inhabitants in the Uruguayan pampas. Despite its size and location, it houses four galleries with international reputations.

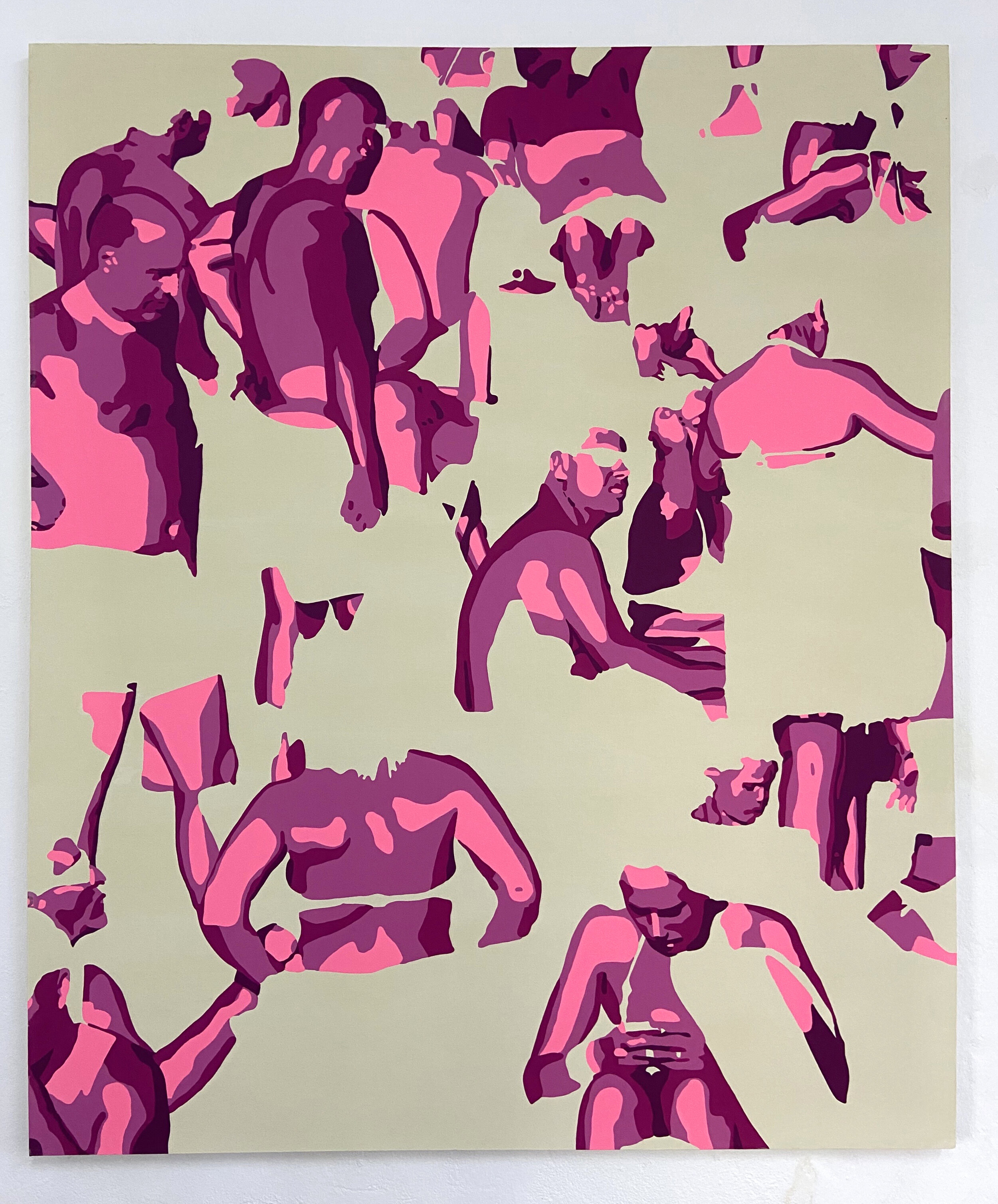

Through large canvases and a predominance of bright pink, she depicts various situations of anonymity by deconstructing bodies and juxtaposing them to create a pattern of evasiveness. As such, Lopez Aldao achieves an ensemble of seemingly innocuous behaviours, but induces an uncomfortable contrast between beauty and threat.

“I combine work with pleasure a lot. Here, January is the month of great tourism, and on the beach it’s very packed. A synergy of activity is generated that I find very attractive and take advantage of in my art.”

For her, beaches have been a recurrent topic for over ten years. Her creative process begins as she photographs these locals and their mundane activities from afar, portraying them in an anonymous way. Reconstructing our past memories, her paintings have the power to contrast reassurance and concern. By seeing our loved ones in these familiar characters, both fragmented and superimposed with one another, the series grimly reminds us of how our recollections can get attenuated and lost all together over time.

“These are environments that I consider very authentic. My research is not on the typical Punta del Este seaside littered with large-scale resorts. I am, however, interested in the "alternative”: that which is more low-profile…where I see more truth. That does not mean that the same truth does not show many things that we dislike: fragmentation, individuality, the feeling of isolation amongst a crowd of people.”

The paintings are enhanced by her installation, Momento Apremiante (2019), which somewhat depicts a coral reef. These congregates gather around the room, playfully inviting viewers into a space of apparent comfort, with pink, violet and black shades that meander to the paintings. When one looks closely, the viewer will notice that the “reef” is composed of thousands of mutilated humanoid figures clustered into these herds. Challenging the visitor’s initial approach, the same pieces that seemed initially attractive become worrying structures that hinder the flow around the room. They inundate the gallery, and the visitor’s role in this dynamic is not clear: am I one of them or am I simply a voyeur?

Lopez Aldao’s exhibition clearly alludes to Venice Biennale’s Lithuanian Pavilion, Sun and Sea (Marina) (2019) by Lina Lapelyte, Vaiva Grainyte and Rugile Barzdziukaite, an opera-performance that blurs the line between reality and fiction by imitating a classical beach scene. Viewers witness the piece from a mezzanine, as performers sing solemn yet humorous lyrics to gentle music. This composition seems both an ode and a requiem to the beach, as the attractive carefreeness of the characters turns into carelessness. From upstairs, visitors are not overwhelmed by the play’s message. However, they are invited to reflect on their relationship with the beach: to see themselves through the actions of these performers. By drawing attention to common behaviours and their impact, the artwork catalyses the profundity of these changes.

The beach is extremely relatable due to its universality, which builds a common ground for viewers to reflect upon. The setting dovetails with human history, personified through actions, developments and regressions. It could be defined as a liberal environment of public belonging. As such, the beach reflects inherent societal values, whether functioning as a meeting point, battlefield, or a space for introspection and reflection.

When asked about the relevance of the beach in art, she expresses her personal concern with its sustainability:

“The beach is the most exploited resource. In this country, there are many paper mills that, together with deforestation of lands, are generating ecological disasters. This is just one of many cases of exploitation and abuse of natural resources that we have in our country. All the residues from agriculture and agrochemicals end up falling into the sea.”

Lopez Aldao’s vocalisations of climate change are harsh and straightforward, yet she conveys this opinion in a much more subtle and convoluted way through her art. From a superficial standpoint, her art portrays the joys and celebrations of the beach. However, if you look deeper, a gradual paradigm shift cuts to a competing dichotomy, just like our self-contradictory actions on climate change. She essentially asks: what are we going to do now? While Multitud en Garzón leaves the viewer with more questions than answers, it clearly pushes us to think twice about our actions, or else we risk trading our joyful memories with stern images of the environmental consequences of our instant gratification.